|

COVID-19 is not the first health crisis to affect Canada. Previous emergencies, like the Lac-Mégantic train tragedy in 2013, showed the importance of including the affected communities to promote better adherence to preventive measures and build resilient communities. Our research shows this is largely missing for COVID-19, with high costs on society as a whole.

Resilience is the ability of a community to continue to live, function, develop and thrive after a crisis. Key elements of enhancing resilience include maximizing social cohesion, collaboration, empowerment, participation and consideration of local characteristics and issues. This means dialogue with, and inputs from, the affected communities.

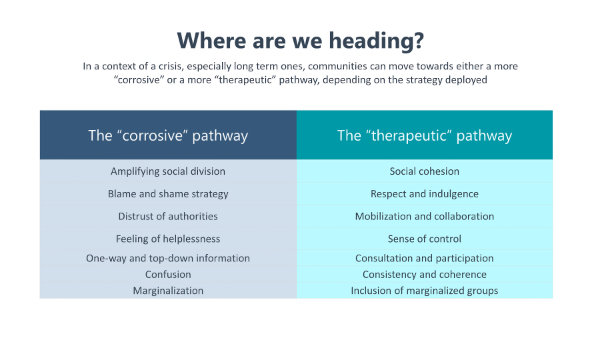

There is a major risk of a community becoming “corrosive” if these elements are not appropriately taken into account. Corrosive communities are at risk of division, polarization and psychological impacts such as anxiety and depression. These are the costs Canadians may have to pay for the divisive approach used in response to COVID-19.

The corrosive versus therapeutic pathway in crisis response. (Blouin-Genest, Généreux, Roy), Author provided

Our multidisciplinary research team at the University of Sherbrooke has been using surveys to evaluate and compare the different effects of the COVID-19 pandemic since February 2020. Different waves of national and international surveys confirm our original findings: the psychosocial impact of the pandemic and responses to it are immense.

Unfortunately, the governmental approach is still divisive, using arguments such as the 90 per cent vaccinated are paying for the inaction of the 10 per cent unvaccinated, that some might be subject to more restrictive measures than others, or that vaccine hesitancy is only prompted by conspiracy seekers and non-believers of science, which is contradicted by our data showing that one-third of unvaccinated people do not hold these beliefs.

This “us against them” strategy is amplifying social division and has major psychosocial impacts, including stress and mental health issues. Our data indicates that this strategy has resulted in a significant decrease in trust toward public health authorities and governments.

Pandemic fatigue

We conducted our most recent survey online from Oct. 1-17, 2021 among 10,368 adults from all regions of Québec and 1,001 adults in the rest of Canada. The results showed half of the adults from across Canada (and, in Québec, nearly two-thirds of young adults) suffer from “pandemic fatigue.”

Pandemic fatigue is a normal and expected response to chronic adversity, but when exacerbated, it can jeopardize not only how we, as communities, respond to the current crisis, as shown by our data, but also how we will react to future ones — a key ingredient in building resilient communities.

Our results showed pandemic fatigue manifests itself through anxiety, depression and suicidal thoughts, issues affecting 21.9 per cent, 25.6 per cent and 9.4 per cent of Canadians, respectively.

The ‘public’ in public health

There is an urgent need to rebuild a safe public space. The population and its representatives (including opposition parties, citizens’ groups and community leaders) need access to sufficient information to monitor the government’s actions, including real-time and raw COVID-19 data. They need to be able to offer criticism and propose alternative solutions, but also feel accepted despite their different viewpoints on the crisis. We must allow a return of the “public” in public health.

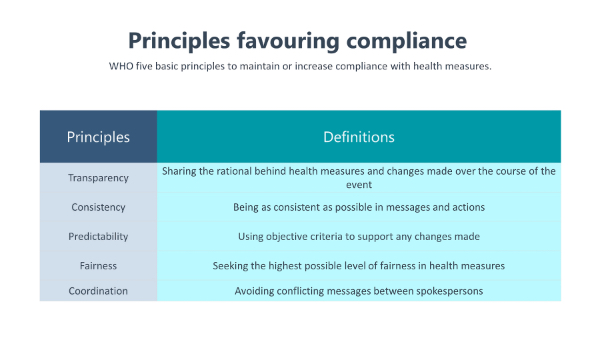

As underlined by the World Health Organization (WHO), governments should act in such a way that citizens and communities can regain some form of power and autonomy in their daily lives. They must feel and perceive that they are seen as legitimate citizens, even when they disagree with the government. This should be guided by five major principles: transparency, consistency, predictability, fairness and co-ordination.

The World Health Organization’s principles favouring compliance. (Blouin-Genest, Généreux, Roy), Author provided

The most important challenge, we argue, is one of coherence, where citizens’ questions and criticisms must be addressed directly rather than ignored, deemed irrelevant or used against those asking them. This will help increase the “sense of coherence” of affected populations, a key factor in building resilient communities.

We define a sense of coherence as a “psychological resource that helps to understand a stressful event, to give meaning to it, and to manage it.” The higher the sense of coherence is, the better we can face adversity and stressful events.

For example, our data shows that those with a high sense of coherence are three times less likely to experience anxiety and depression. The sense of coherence can be directly affected by the strategies put in place by governments and authorities to respond to crises. Our data suggests that, overall, Canadians’ sense of coherence decreased during the pandemic.

Dialogue with communities

The health emergency Canada still faces should not be underestimated, and as the WHO reiterates, the pandemic is far from over. However, not all policies and measures need to be implemented through “emergency” procedures or justified by the state of emergency, as seen widely in Canada right now. The response to COVID-19 must rely on a stronger democracy, where citizens and communities can express themselves, exchange and reflect and, by doing so, bring back meaning and coherence in their daily lives.

Dialogue with affected communities is still left aside in responses to the pandemic, amplifying skepticism and beliefs in erroneous information. Our research also underlines an increase in political polarization, deepening already existing gaps between communities.

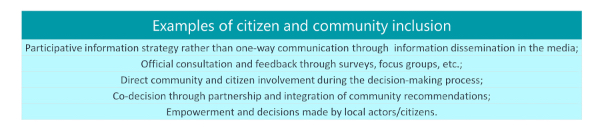

A crisis strategy should not be based on information moving only in one direction. (Blouin-Genest, Généreux, Roy), Author provided

The spectrum of citizen participation can be quite diverse, but our data suggest that the current COVID-19 strategy based on the information moving only in one direction — in which citizens and communities assume very little responsibility — is a wrong one. The recognition of past mistakes, humility and better community involvement should be the cornerstones of our responses to this crisis, with citizen and community inclusion.

Bringing back dialogues between authorities and communities affected by the pandemic is a real emergency. The long-term health of individuals and communities is at stake.

Mélissa Généreux, Associate Professor, Faculty of medicine and health sciences, Université de Sherbrooke ; Gabriel Blouin-Genest, Associate professor, School of applied politics, Scientific codirector, CIDIS (Centre interdisciplinaire de développement international en santé), Université de Sherbrooke , and Mathieu Roy, Professeur associé, Faculté de médecine et des sciences de la santé, Université de Sherbrooke

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. |